Over at The Atlantic, Gregory Clark admits, rather refreshingly, that academic economists have no clothes.

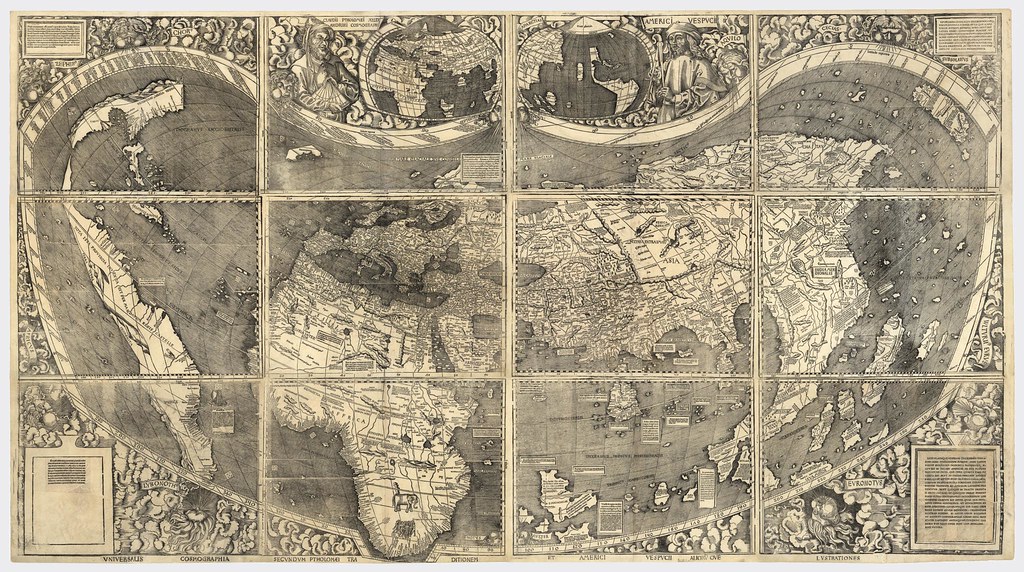

The current recession has revealed the weaknesses in the structures of modern capitalism. But it also revealed as useless the mathematical contortions of academic economics. There is no totemic power.As a discipline, economics proposes models, which are by definition incomplete. That is, they exclude some details and highlight others. To think that economic theories actually describe reality--as opposed to offer an image of reality that is useful for some purposes--is to mistake the map for the world.

Ceci n'est pas le monde.

Further, the dismal science has all too often provided models whose validity is impossible to ascertain, since it has often built its theories on the basis of premises that are false prima facie. The point here is that, logically speaking, false premises do not yield false conclusions; rather, false premises render the truth values of an argument's conclusions indeterminate. It isn't that economic models are false, but rather that the falseness of their premises means that can know nothing with certainty about their conclusions. We can't say whether economic models are true, false, or some determinate mix of the two. Logically speaking, they're mere speculation, with the same logical status as wishful thinking.

You mean we came all this way and we don't even know if we're wrong?

For example, the theories of classical economics generally accept as axioms (i.e., they accept as true without argument) the following:

- All economic actors are rational.

- All economic actors have perfect information about the markets in which they act.

- All resources are scarce.

The debate about the bank bailout, and the stimulus package, has all revolved around issues that are entirely at the level of Econ 1. What is the multiplier from government spending? Does government spending crowd out private spending? How quickly can you increase government spending? If you got a A in college in Econ 1 you are an expert in this debate: fully an equal of Summers and Geithner.Common sense cloaked in jargon and equations. Even the economists' invisible clothes look rather shabby these days.